The jejunum is one of the sections of the small intestine, the length of which is approximately 4-5 meters. The small intestine consists of the duodenum, followed by the jejunum, and only then the ileum. The intestine is covered on all sides by a membrane, which is called the peritoneum and is attached to the posterior wall of the abdomen using the mesentery. The human jejunum is located in the left half of the abdominal cavity. It is projected onto the anterior abdominal wall in the umbilical region, on the sides of the abdomen, and also in the left iliac fossa. The intestinal loops are located in horizontal and oblique directions. The length of the jejunum is 2/5 of the total length of the small intestine. Compared to the ileum, the jejunum has thicker walls and a larger diameter of the internal lumen. It also differs in the number of villi and folds that are located in the lumen, the number of vessels, of which there are more, but, on the contrary, there are fewer lymphoid elements. There are no clear boundaries for the transition of one part of the intestine to another.

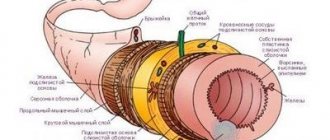

Wall structure

On the outside, the intestine is covered with a special membrane along its entire length.

This is the peritoneum, which protects it and smoothes out the friction of the intestinal loops against each other. The peritoneum converges at the back of the intestine to form the mesentery of the jejunum. It is in it that blood vessels and nerves pass, as well as lymphatic capillaries that feed the intestine and carry away from it not only the nutrients needed by the body, but also toxic breakdown products, which are then neutralized by the liver. The second layer is made up of smooth muscle tissue, which in turn forms two layers of fibers. There are longitudinal fibers on the outside and circular fibers on the inside. Due to their contraction and relaxation, chyme (food that has been exposed to the active substances of the digestive tract in previous sections) passes through the intestinal lumen and delivers all the beneficial substances to the body. The process of sequential contraction and relaxation of fibers is called peristalsis.

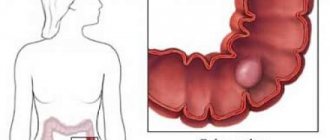

Colon

The large intestine is located around the perimeter of the relatively small intestine and has a frame-like shape, located closer to the abdominal cavities. After food passes through the jejunum and ileum, broken down to the simplest amino acids, and after they are absorbed into the intestinal walls and blood, the rest of the mass, which is based on fibers and cellulose, enters this section. The main function of the large intestine is to absorb water from the remaining mass and form solid feces for removal from the body. Nevertheless, digestion processes continue to occur in it.

The human large intestine is saturated with various microorganisms that help process substances that cannot be absorbed into the human body. Various types of lactobacilli, bifidobacteria and some types of E. coli live here. The content and concentration of such bacteria is responsible for the health of the intestine and its microflora. If any of the types of microorganisms decrease in number or disappear altogether, then dysbacteriosis develops in the body. It can occur in quite severe forms and promotes the development and proliferation of pathogenic microbes and fungi, which not only reduces the level of immunity in general, but can also have serious consequences for the health of the body.

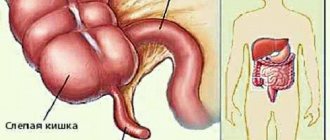

The structure of the human intestine of the large section includes the following intestines:

- blind;

- ascending colon;

- right flexure of the colon;

- transverse colon;

- descending colon;

- sigmoid colon.

The large intestine is much shorter than the small intestine and ranges from one and a half to two meters in length. In diameter it ranges from 7 to 10 centimeters.

Functionally important layer

The previous two layers provide normal function and protection, but the entire process of food absorption occurs in the last two. Under the muscular layer there is a submucosal layer, it is in it that the jejunum has blood lymphatic capillaries and accumulations of lymphatic tissue. The mucous layer protrudes into the lumen in the form of folds, due to which the absorption surface becomes larger. Additionally, the surface of the mucous membrane is enlarged by villi; they can only be seen under a microscope, but their role here is very important. They provide a constant supply of nutrients to the body.

Purpose, structure of the small intestinal mucosa

The main task of the intestinal mucosa is the next stage of breakdown of nutrients by enzymes of intestinal juice with further release of processed products into the blood, subsequent transport to the body’s cells.

Additionally, the villi of the mucous membrane protect the processed food mass from the penetration of toxins and microorganisms. A special feature of the structure of the organ created by nature is its small total area of 0.58–0.72 m², which increases during operation five to seven times, up to 5.5 m².

During meals, the movement of the villi ensures maximum absorption of the nutritional mixture. Chemical and mechanical irritants also set the villi in motion, providing antimicrobial, antitoxic protection for the body.

Various reasons lead to deterioration in the functioning of the small intestinal mucosa. What should you pay attention to first?

Villi

Villi are processes of the mucous membrane, the diameter of which is only one millimeter. They are covered by cylindrical epithelium, and in the center there are lymphatic and blood capillaries. Also, the glands that are located in the mucosa secrete many active substances, mucus, hormones, enzymes, which contribute to the process of digesting food. The capillary network simply penetrates the mucosa and passes into venules, merging, they, together with other vessels, form the portal vein, which carries blood to the liver.

What parts of the intestine are there?

Experts distinguish between 2 main sections of the intestine: the small and large intestines. In turn, each of them includes:

- thin - duodenum, jejunum and ileum;

- thick – cecum, colon, sigmoid, rectum.

The large and small intestine differ from each other in structure and function. Thus, in the small intestine, food is predominantly digested and nutrients are absorbed, and in the large intestine, water is absorbed and feces are formed. In this regard, the small intestine has a smoother surface and a smaller lumen diameter, and the large intestine is wider and collected in special folds - haustra.

Function performed by the jejunum

The main function of the intestine is the processing and absorption of food that has been previously processed by previous sections of the digestive tract. The food here consists of amino acids, which were once proteins, monosaccharides, which were once carbohydrates, as well as fatty acids and glycerol (what lipids have become). The structure of the jejunum provides for the presence of villi, it is thanks to them that all this enters the body and can be used as nutritional material. Amino acids and monosaccharides enter the liver, where they are further transformed and subsequently enter the systemic circulation, fats are absorbed by lymphatic capillaries, and then enter the lymphatic vessels, and from there they disperse throughout the body with the lymph flow. Everything that has not passed the test for usefulness in the jejunum ends up in further sections of the intestine, in which feces are finally formed.

Small intestine

Small intestine

(lat.

intestinum tenue

) - a section of the gastrointestinal tract located between the stomach and large intestine. Together with the large intestine, they make up the intestines. The name of the small intestine is due to the fact that its walls are less thick and durable, and the internal diameter of its lumen is smaller than that of the large intestine.

Anatomy of the small intestine

The small intestine has three sections: duodenum (lat. duodenum

), jejunum (lat.

jejunum

) and ileum (lat.

ileum

). The jejunum and ileum do not have a clear boundary between each other. Typically, the first 2/5 of the total length is allocated to the jejunum, and the remaining 3/5 to the ileum. At the same time, the ileum has a larger diameter, its wall is thicker, and it is richer in blood vessels. in relation to the midline, the loops of the jejunum lie mainly on the left, the loops of the ileum on the right. The small intestine is separated from the upper parts of the digestive tract by the pylorus, which acts as a valve, and from the colon by the ileocecal valve.

The thickness of the wall of the small intestine is 2–3 mm, and during contraction it is 4–5 mm. The diameter of the small intestine is not uniform. In the proximal part of the small intestine it is 4–6 cm, in the distal part it is 2.5–3 cm. The small intestine is the longest part of the digestive tract, its length is 5–6 m. The weight of the small intestine of a “conditional person” (with body weight 70 kg) normal - 640 g.

The small intestine occupies almost the entire lower floor of the abdominal cavity and partially the pelvic cavity. The beginning and end of the small intestine are fixed by the root of the mesentery to the posterior wall of the abdominal cavity. The rest of the mesentery ensures its mobility and position in the form of loops. They are bordered on three sides by the colon. Above is the transverse colon, on the right is the ascending colon, on the left is the descending colon. The intestinal loops in the abdominal cavity are located in several layers, the superficial layer is in contact with the greater omentum and the anterior abdominal wall, the deep layer is adjacent to the posterior wall. The jejunum and ileum are covered on all sides by peritoneum.

The structure of the wall of the small intestine

The wall of the small intestine consists of four membranes (often the submucosa is referred to as the mucous membrane and then the small intestine is said to have three membranes):

- mucous membrane, divided into three layers:

- epithelial

- lamina propria, which has depressions - Lieberkühn's glands (intestinal crypts)

- muscle plate

The mucous membrane of the small intestine has a large number of circular folds, most clearly observed in the duodenum. The folds increase the absorptive surface of the small intestine approximately threefold. In the mucous membrane there are lymphoid formations in the form of lymphoid nodules. If in the duodenum and jejunum they are found only in a single form, then in the ileum they can form group lymphoid nodules - follicles. The total number of such follicles is approximately 20–30.

Functions of the small intestine

The most important stages of digestion occur in the small intestine.

The mucous membrane of the small intestine produces a large number of digestive enzymes. Partially digested food, chyme, coming from the stomach, is exposed in the small intestine to intestinal and pancreatic enzymes, as well as other components of intestinal and pancreatic juices, bile. In the small intestine, the main absorption of food digestion products into the blood and lymphatic capillaries occurs. The small intestine is also where most orally administered drugs, poisons and toxins are absorbed.

The normal residence time of the contents (chyme) in the small intestine is about 4 hours.

Functions of various parts of the small intestine (Sablin O.A. et al.):

| Duodenum | Jejunum | Ileum |

| Release of enzymes, hydrolysis of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, enrichment of chyme with bile, change in acidity of the medium, mixing of contents and its transport, absorption | Hydrolysis of polymers, endocrine, absorption, motor, evacuation, hormonal | Absorption of hydrolysis products, bile acids, immune, endocrine, motor-evacuation |

Endocrine cells and hormone content in the small intestine

The small intestine is the most important part of the gastroenteropancreatic endocrine system.

It produces a number of hormones that regulate the digestive and motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract. The proximal parts of the small intestine contain the largest set of endocrine cells among other organs of the gastrointestinal tract: I-cells producing cholecystokinin, S-cells - secretin, K-cells - glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), M-cells - motilin, D -cells - somatostatin, G-cells - gastrin and others. The liberkühn glands of the duodenum and jejunum contain the vast majority of all I cells, S cells and K cells in the body. Some of the listed endocrine cells are also located in the proximal part of the jejunum and an even smaller part in the distal part of the jejunum and in the ileum. In the distal part of the ileum there are, in addition, L-cells that produce the peptide hormones enteroglucagon (glucagon-like peptide-1) and peptide YY. The content of hormones (in pmol/g) and the number of cells of their producers per 1 mm2 in the sections of the small intestine (SRBloom, JMPolak; G.F. Korotko):

| Sections of the small intestine | ||||

| Hormone | duodenum | skinny | ileum | |

| gastrin | gastrin content | 1397±192 | 190±17 | 62±15 |

| number of producing cells | 11–30 | 1–10 | 0 | |

| secretin | secretin content | 73±7 | 32±0,4 | 5±0,5 |

| number of producing cells | 11–30 | 1–10 | 0 | |

| cholecystokinin | cholecystokinin content | 26,5±8 | 26±5 | 3±0,7 |

| number of producing cells | 11–30 | 1–10 | 0 | |

| pancreatic polypeptide (PP) | PP content | 71±8 | 0,8±0,5 | 0,6±0,4 |

| number of producing cells | 11–30 | 0 | 0 | |

| GUI | GUI content | 2,1±0,3 | 62±7 | 24±3 |

| number of producing cells | 1–10 | 11–30 | 0 | |

| motilin | motilin content | 165,7±15,9 | 37,5±2,8 | 0,1 |

| number of producing cells | 11–30 | 11–30 | 0 | |

| enteroglucagon (GLP-1) | GLP-1 content | 10±75 | 45,7±9 | 220±23 |

| number of producing cells | 11–30 | 1–10 | 31 | |

| somatostatin | somatostatin content | 210 | 11 | 40 |

| number of producing cells | 1–10 | 1–10 | 0 | |

| VIP | VIP content | 106±26 | 61±17 | 78±22 |

| number of producing cells | 11–30 | 1–17 | 1–10 | |

| neurotensin | neurotensin content | 0,2±0,1 | 20 | 16±0,4 |

| number of producing cells | 0 | 1–10 | 31 | |

Small intestine in children

The small intestine in children occupies a variable position, which depends on the degree of its filling, body position, intestinal tone and peritoneal muscles. Compared to adults, it is relatively long, and the intestinal loops lie more compactly due to the relatively large liver and underdevelopment of the pelvis. After the first year of life, as the pelvis develops, the location of the loops of the small intestine becomes more constant. The small intestine of an infant contains relatively a lot of gases, which gradually decrease in volume and disappear by the age of 7 (adults normally do not have gases in the small intestine). Other features of the small intestine in infants and young children include: greater permeability of the intestinal epithelium; poor development of the muscle layer and elastic fibers of the intestinal wall; tenderness of the mucous membrane and a high content of blood vessels in it; good development of villi and folding of the mucous membrane with insufficiency of the secretory apparatus and incomplete development of the nerve pathways. This contributes to the easy occurrence of functional disorders and facilitates the penetration into the blood of undigested food components, toxic-allergic substances and microorganisms. After 5–7 years, the histological structure of the mucous membrane no longer differs from its structure in adults (Bokonbaeva S.D. et al.).

Small intestine in newborns

A newborn has a relatively large length of the small intestine: 1 m per 1 kg of body weight, and 10 cm in adults. Due to the relatively large size of the liver and underdevelopment of the pelvis, the intestinal loops lie more compactly than in adults.

The small intestine is where most of the digestion and absorption of food occurs. The small intestine of an infant contains a relatively large amount of gases, the volume of which gradually decreases until it completely disappears by the age of 7 (adults normally do not have gases in the small intestine).

The mucous membrane is thin, richly supplied with blood vessels and has increased permeability (especially in children of the first year of life). In newborns, single and group lymphoid follicles are present in the thickness of the mucous membrane. Initially, they are scattered throughout the intestine, and subsequently are grouped mainly in the ileum in the form of group lymphatic follicles (Peyer's patches). Lymphatic vessels are numerous and have a wider lumen than in adults. Lymph flowing from the small intestine does not pass through the liver, and absorption products enter directly into the blood (Geppe N.A., Podchernyaeva N.S.).

Some diseases of the small intestine

Some diseases of the small intestine and syndromes (see):

| Inflammatory process in the small intestine |

- enteritis

- small bowel cancer

- duodenitis

- gastroduodenitis

- gurgles

- duodenal ulcer

- functional dyspepsia, including dyspepsia in children

- helminthiasis:

- hookworm (hookworm, necatoriasis)

- strongyloidiasis

- taeniasis and teniarinhoz

- diphyllobothriasis

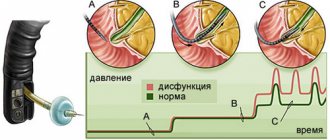

Duodenal motility disorders:

- duodenal hypertension

- duodenal obstruction

Some symptoms that may be associated with diseases of the small intestine:

- stomach ache

- nausea

- vomit

- flatulence

- diarrhea (diarrhea), including diarrhea (diarrhea) in children

- melena

On the website in the “Literature” section there is a subsection “Diseases of the small intestine”, containing publications for healthcare professionals, including issues of diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the small intestine. Back to section

From normal to disease - one step

The jejunum has many functions and, in the absence of malfunctions or diseases, functions normally without causing any special problems. But if a failure occurs, then it is worth contacting a specialist in time. It is difficult to examine the jejunum, like the entire small intestine, and tests are of great importance. First of all, it is worth examining feces, which can tell what kind of malfunction occurred in the intestines. But a banal examination and palpation (palpation) will also not be superfluous.

There can be a lot of options for problems in the jejunum, but the main place is occupied by pathology of a surgical, therapeutic and infectious nature. Treatment depends on this, as well as the choice of a specialist who will help get rid of the disease.

Prevention measures

Paying attention to your diet will help protect the duodenum from damage.

- You should not eat food that is too hot or too cold.

- Chew food thoroughly so that the pulp enters the duodenum, because the stomach and intestines do not have teeth.

- You should not wash down food with cold drinks, as this opens the sphincter, and all food enters the duodenum undigested by gastric juice.

- Eat food in a good mood and without rushing.

- Monitor normal stomach acidity.

- Follow the rules of hygiene - wash your hands and food.

https://youtu.be/VQua_8pjJPA

Other diseases

The jejunum can bring many problems that the surgeon will have to deal with. Sometimes delay in making the correct diagnosis can lead to the death of the patient. Consider Crohn's disease, which can result in bleeding, abscesses and other complications. Some ailments can lead to dysfunction of the jejunum, and in order to restore them, surgery is also required. For example, adhesions in the abdominal cavity, especially in places where this section of the small intestine is located, may require surgical excision of adhesions. Surgical treatment tactics are also used for helminthic infestations, when the lumen is clogged with a ball of helminths.

General symptoms of the disease

Depending on the severity, signs of the disease appear as:

- Painful attacks in the abdomen, manifested by periodic contractions.

- Liquid stool 2-3 times a day.

- Stable alternation of diarrhea and constipation.

- Painful reaction to manual examination of the small intestine.

- Sensations of fluid transfusion in the intestines when the position of the body changes.

- Reducing body weight.

Important! Due to the similarity of the signs of the gastrointestinal tract disease, the exact diagnosis is determined by a hepatologist.

The listed symptoms indicate the appearance of inflammatory processes in the mucous membrane of the small intestine, the occurrence of one of the types of gastrointestinal diseases.

Why should you go to a therapist?

The therapist also has some work to do. He, of course, has less work than a surgeon, but it is no less responsible. All diseases and inflammatory changes occurring in the jejunum fall on the shoulders of this specialist. These are colitis, which can be acute and chronic, irritable bowel syndrome and other pathologies. The use of a scalpel for these diseases is not required, but competently and correctly prescribed treatment will help get rid of the disease and restore the joy of life.

The infection does not sleep

It is no secret that the jejunum contains a huge number of microorganisms in its lumen. Some of them are good and beneficial to the body, but there are also bad ones that constantly try to cause harm. The immune system holds back the onslaught of pathogenic microflora, but sometimes it fails to cope with its main task, and then infectious diseases begin. Often the body may have unwanted neighbors; helminths strive to get into an excellent habitat, which is the jejunum for them.

Many diseases can develop in the lumen of the small intestine, such as dysentery, cholera, typhoid fever, salmonellosis and many others. The symptoms they cause vary, but one thing they have in common is diarrhea. It can have a different color and smell, be with or without impurities, as well as blood or water. The final point in determining the pathogen will be made by bacteriological examination of the excreted material. Then, based on the sensitivity of the pathogen to antibacterial drugs, appropriate treatment is prescribed. It is also possible to identify helminths; to do this, you should have your stool tested, and only an infectious disease specialist can help you get rid of them.